Hello President Trump: Let’s Not Repeat the Economic Tragedy of the 2010s in the 2020s

If President Trump wants to bring the economy quickly back to full employment, he will have to confront the Establishment wing of his Republican party. The clash – if it comes – will be over Establishment Republican hostility to  government spending. More spending will be needed to bolster an economy staggering under the blows of the COVID19 pandemic and the BLM/Antifa riots, as well as for the public investment in infrastructure, innovation, and worker skills required to lift America’s long-run growth potential. In the 2016 election, Mr. Trump did well to break with Establishment Republican orthodoxies on globalization, trade, and immigration. He should break with their worn-out doctrines on macroeconomics as well.

government spending. More spending will be needed to bolster an economy staggering under the blows of the COVID19 pandemic and the BLM/Antifa riots, as well as for the public investment in infrastructure, innovation, and worker skills required to lift America’s long-run growth potential. In the 2016 election, Mr. Trump did well to break with Establishment Republican orthodoxies on globalization, trade, and immigration. He should break with their worn-out doctrines on macroeconomics as well.

All this may be delusion on my part, I admit. Mr. Trump himself appears to have no ideological fixation against public spending and debt. But, as an isolated outsider in Washington, he depends on the Republican Establishment, its think tanks, lobbyists, and personnel for policy ideas and expertise. These are people for whom spending cuts, tax cuts, free trade, and deregulation have been the summit of all wisdom since at least the Reagan era forty years ago, a faith impervious to evidence or argument. Buoyed by the unexpectedly strong May jobs report, the amiable Establishment types in Trump’s economic team could well talk him into a premature end of stimulus, or into wasting fiscal resources on tax cuts with only modest economic benefits. However, econometrician James Hamilton warns that, while “the good news is quite real,” problems in data measurement and classification mean that May unemployment was “more like 19.8% than the reported 13.3%,” so that “we still have a long, long way to go.”

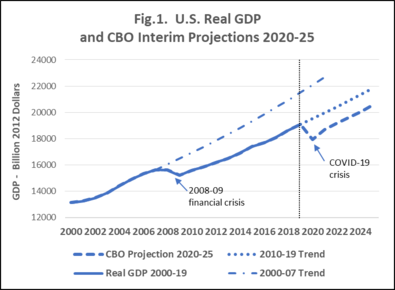

The Congressional Budget Office’s recent Interim Economic Projections, which assume no additional stimulus, paint the picture of a U.S. economy that fails to recover fully from the COVID19 crisis. (Figure 1.) The CBO expects a 6% GDP contraction in 2020, followed by a little over 4% growth in 2021. That would leave U.S. GDP next year still smaller than in 2019, and well below where the economy would have been in 2021 without coronavirus. Indeed the projections show an economy that never returns to its previous growth path. The CBO expects this long-term malaise despite assuming a strong rebound in the third and fourth quarters this year, a scenario Democrats fear might help President Trump win reelection in November.

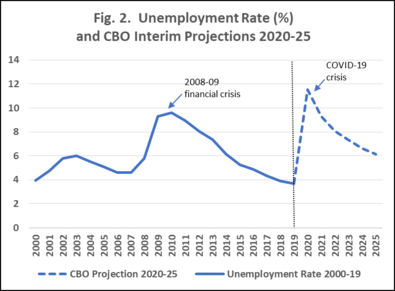

The CBO projections for COVID-19 look remarkably like the aftermath of the 2008-09 financial crisis, although the two events had different causes. Then the economy also fell permanently below its pre-recession path so that tens of trillions of dollars of potential output and income were lost. (Figure 1 above.) Median family incomes fell and were no higher in 2015 than in 2000. The unemployment rate surged to over 9 percent in 2010, and stayed high for years, bringing in its train a high toll in wasted lives, stress, ill-health, drug addiction, family disintegration and premature death. (Figure 2.)

The weak growth and persistently high unemployment that followed the financial crisis were, in part, the result of one of the great policy blunders of modern times, a  consensus among Western elites to reverse fiscal stimulus at a time when the recovery had hardly begun. But the purported dangers of government deficits - an unsustainable debt spiral, soaring interest rates, and high inflation - had little basis in either fact or theory. Instead, research suggests that premature fiscal consolidation not only put economies on a permanently lower growth path, but it also increased government indebtedness.

consensus among Western elites to reverse fiscal stimulus at a time when the recovery had hardly begun. But the purported dangers of government deficits - an unsustainable debt spiral, soaring interest rates, and high inflation - had little basis in either fact or theory. Instead, research suggests that premature fiscal consolidation not only put economies on a permanently lower growth path, but it also increased government indebtedness.

Let’s not underrate the capacity of the American political class to deliver another such disaster in the wake of the coronavirus crisis, of the sort depicted in the CBO projections.

Notwithstanding the outcome of the election, a new nationalist and populist center-right American politics must be realistic about the flaws of market economies. For all their enormous benefits in promoting competition, innovation, and liberty, market economies are not always great at pulling themselves out of recession and returning quickly to full employment. Monetary and fiscal policies can help fix these flaws, spread the benefits of, and sustain political support for free markets. Plentiful jobs and rising wages are among the strongest bulwarks against the extraordinarily destructive, violently authoritarian, anti-national, racially divisive, and socially corrosive agendas of the modern American left that have burst into such evil flower in the present election cycle. Devising a practical, rule-bound framework for full employment and macroeconomic stability ought to be near the center of a new nationalist and populist center-right economic program.

Paths out of COVID-19: short-term strong, longer-term weak

The U.S. economy’s path out of COVID19 will be complicated, with more than one twist and turn. The economy, having crashed into recession faster than ever before, is also likely to rebound more quickly than before. But there are reasons why the crisis could also have more persistent effects, causing the recovery to peter out before the economy regains full employment.

Unlike the financial crisis of 2008-09, this was not a recession brought on by a lack of aggregate demand. The COVID-19 crisis started with a sudden, massive supply shock, a temporary shutting down of so-called “non-essential services” intended to save lives by stopping or slowing the transmission of the coronavirus. By the same token, as Jason Furman, chair of President Obama’s Council of Economic Advisers, observes, when the “non-essential” economy begins to reopen, the recovery:

“can be very very fast, because people go back to their original job, they get called back from furlough, you put the lights back on in your business. Given how many people were furloughed and how many businesses were closed you can get a big jump out of that. It will look like a V.”

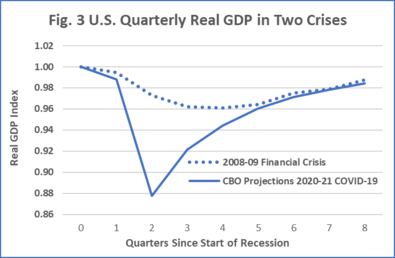

The CBO projects just such a strong rebound in the second half of 2020. (Figure 3.) After falling an annualized 38% in the second quarter, real GDP rebounds 22% in the third quarter and 10% in the fourth. But the CBO also expects the pace of the recovery  to slow in 2021. The trajectory of GDP becomes almost indistinguishable from its path in the weak recovery after the 2008-09 financial crisis. In the fourth quarter of 2021, GDP would remain 2% below the fourth quarter of 2019, and far below where it would have been without COVID-19. The unemployment rate would still be near 9%.

to slow in 2021. The trajectory of GDP becomes almost indistinguishable from its path in the weak recovery after the 2008-09 financial crisis. In the fourth quarter of 2021, GDP would remain 2% below the fourth quarter of 2019, and far below where it would have been without COVID-19. The unemployment rate would still be near 9%.

Other forecasters concur with the CBO’s “short-term strong, long-term weaker” path for the economy. Moody’s Analytics baseline scenario concludes it will take until mid-decade for the economy to return to full employment, assuming Congress and the President agree soon on an additional $1 trillion fiscal package before the end of the year. Without such support, Moody’s predicts the U.S. economy will fall back into recession in late 2020 and early 2021.

There are several reasons why the COVID19 shock is likely to have persistent depressing effects on the economy. The course of the pandemic itself remains highly uncertain, with the potential for second or more waves to affect behavior perhaps for years. Business bankruptcies and failures are already surging, and it will take years to work through the defaults and foreclosures. Whole industries like air travel, tourism, hotels, restaurants, and big-box retailing are likely to downsize permanently, and it may take years for new industries and businesses to come up, and for unemployed workers to find new jobs. Supply shocks like COVID-19 can depress aggregate demand by even more than the initial shock and become self-perpetuating. Households, battered by two giant crises within fifteen years, could become permanently less confident and more risk-averse about the future, boosting savings at the expense of consumption. Businesses, concerned about poor consumer demand, would delay investment and hiring, confirming the fears of households, landing the economy in a self-fulfilling high-unemployment trough.

Deep recessions and persistently weak growth, in turn, degrade the productive supply capacity of the economy, through so-called hysteresis effects. Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell, who thinks the Fed and the government should supply as much  monetary and fiscal stimulus as needed to ensure a robust recovery, is eloquent on this point:

monetary and fiscal stimulus as needed to ensure a robust recovery, is eloquent on this point:

“The record shows that deeper and longer recessions can leave behind lasting damage to the productive capacity of the economy. Avoidable household and business insolvencies can weigh on growth for years to come. Long stretches of unemployment can damage or end workers’ careers as their skills lose value and professional networks dry up, and leave families in greater debt. The loss of thousands of small- and medium-sized businesses across the country would… limit the strength of the recovery when it comes… A prolonged recession and weak recovery could also discourage business investment and expansion, further limiting the resurgence of jobs as well as the growth of capital stock and the pace of technological advancement. The result could be an extended period of low productivity growth and stagnant incomes.” (Jerome Powell, speech on “Current Issues,” May 13, 2020.)

Could the U.S. blunder into another decade of economic stagnation?

In short, although the COVID19 crisis had a very different cause from the financial crisis of 2008-09, it could end up having the same result: “an extended period of low productivity growth and stagnant incomes,” in particular if we were to repeat the economic policy blunders of the earlier crisis. A brief detour into the policy aftermath of the 2008-09 financial crisis is informative at this point.

For one thing, the fiscal stimulus proposed by the incoming Obama administration in early 2009 was just too small. Despise his political fanaticism as one may, Paul Krugman foresaw this outcome with impressive prescience even before President Obama had taken office. Using some back-of-the-envelope Keynesian calculations, he concluded that the stimulus package of $775 billion over two years would do something but not enough to limit unemployment, correctly predicting that the unemployment rate would peak at around 9% and come down only slowly.

Then, in 2010 – only ten years ago! - there occurred one of the most far-reaching policy errors of modern times, the emergence of a consensus among Western elites on the immediate dangers of fiscal deficits, demanding austerity at a time when the recovery had hardly begun.

The European Union led the charge for premature fiscal consolidation at the international “Group of Twenty” (G20) meeting in Toronto in June 2010. To its credit, the Obama administration argued for continued fiscal stimulus but, characteristically, without much conviction: the communique of the G20 meeting committed advanced economies to halve fiscal deficits by 2013. The Republican takeover in Congress at the end of 2010 completed the U.S. turn to premature austerity.

Figure 4 shows the IMF’s ‘fiscal impulse’ measure, which is the change in the (cyclically adjusted) fiscal deficit as a % of GDP. For three years in 2008-10, the U.S.  fiscal impulse was appropriately in the direction of economic stimulus. But for three years in 2011-13, it was set even more powerfully towards contraction, stopping unemployment from falling below 8-9%.

fiscal impulse was appropriately in the direction of economic stimulus. But for three years in 2011-13, it was set even more powerfully towards contraction, stopping unemployment from falling below 8-9%.

The supporters of austerity at the time said that fiscal deficits were both ineffective and would cause an unsustainable rise in government debt. Panicky financial markets would sell government bonds, powering a surge in interest rates that would crowd out private investment and throw the economy back into recession. A group of 24 economists warned the Federal Reserve that its attempts to support the economy through “quantitative easing” would only “risk currency debasement and inflation.”

We’ll return to how these claims turned out to be unsupported by either facts or economic theory. But consider first if the U.S. might blunder its way into another decade of economic stagnation through another premature turn to fiscal austerity.

Some Republican senators were already denouncing deficits and debt in the spring, with the economy still in freefall. Thus Senator Pat Toomey of Pennsylvania:

“In the past two months, Congress spent nearly $3 trillion and authorized the Fed to lend well over $2 trillion more to stave off an economic collapse. This is more than one-quarter of our entire annual GDP. As a result, our national debt is about to hit $25 trillion, our deficit this year will be double the worst year of the financial crisis, and we are risking higher interest rates and inflation. Rather than yet another spending blowout, Congress should focus on re-opening our economy safely. Government spending can never be a substitute for a functioning economy.”

Stephen Moore - an economic adviser to the White House, sadly - was quick to claim the upbeat May jobs report proved there was no need for more coronavirus fiscal relief. The establishment-conservative media and think tanks have taken up their customary chanting on the perils of deficits and debt. The Heritage Foundation warns of “America’s Dual Nightmare: Coronavirus and Massive Debt.” It recommends that any government responses to the pandemic must avoid debt, given the danger of “a public debt crisis. ” Amazingly, a National Coronavirus Recovery Commission created by the Heritage Foundation could find no better economic recommendation for coronavirus than more globalization: “removing barriers to free trade,” elimination of the trade tariffs imposed by President Trump, and the pursuit of free trade agreements. National Review digs up and drags on to the carpet ancient, fallacious and long since refuted arguments about the logical impossibility of fiscal stimulus.

You can see how the politics of fiscal austerity might play out over the coming year. Stimulus opponents will clamor that a strong recovery in the second half of 2020 proves there was no need for stimulus anyway, and certainly no need for one going forward. If the recovery peters out in 2021, as the CBO and others predict, with still high unemployment, stimulus opponents will find no cause to change their opinion. At that point, the cry will be that we can’t afford any more stimulus because of the record, unsustainable level of government debt, opening the way for a repetition of the policy blunders and the economic tragedy of the 2010s in the 2020s.

It will be curious to see whether President Trump has the wit and the will to face down the Establishment Republicans, or if he will knuckle under and go along. One can’t underestimate the influence of the Establishment. Still, there may be a few reasons for hope.

First, President Trump is justifiably proud of the strong economy just before COVID19, with unemployment the lowest in 30 years and significant wage gains for low-income workers and minorities. He wants to restore that economy, not in some hazy future, but now, which is the right instinct to have. Second, his administration had no qualms in putting through the most massive deficit spending package in American history earlier this year, a good sign. Third, there is the emergence of an explicitly nationalist, populist and activist wing in the Republican Party. Ryan Lizza says in Politico magazine:

“The two most notable politicians crafting stimulus policy for Trump to sign are Republican Sens. Marco Rubio of Florida and Josh Hawley of Missouri. Before the coronavirus crisis, both senators had taken stabs at articulating a new kind of policy populism for the GOP that was self-consciously anti-libertarian, skeptical of Big Business, and more comfortable with Big Government…

Before the crisis, Rubio, Hawley and their fellow Republican populists…seemed to amount to little more than a small group of legislators, a tight network of D.C. policy wonks, and some right-leaning opinion columnists. But when the pandemic struck, they were suddenly crafting the most consequential and interventionist legislation of the century.”

There’s even a new think tank, American Compass, patronized by the likes of Marco Rubio and Tom Cotton, that champions a robust conservative-nationalist economic agenda while attacking the “free-market fundamentalist” and “economic libertarian” ideology still dominant in today’s Republican Party.

An ideology unsupported by evidence or argument

Consider, first, claims that fiscal stimulus will be merely ineffective at boosting jobs and the economy while creating distortions that will hurt growth in the longer term.

This claim is a partial truth at best. It’s true that when the economy is already at full employment, then government spending obviously cannot boost output and jobs much in the near-term, at least without creating inflationary pressures. At full-employment, spending on government consumption can also hurt the economy long-term, by diverting resources from the private sector that would have gone into saving and into investment in productive capital. It is this reduction in the capital stock and potential future output that we mean by the phrase ”the burden of debt on future generations.”

It is different when the economy is in recession, with high unemployment and spare capacity. Now stimulus spending and borrowing do not divert resources from some fixed pool of private saving and investment. Instead, as straightforward Keynesian arguments show, they create jobs and increase income, which boosts both consumption and saving. These new savings help fund both the government deficit and new investment. More investment creates a bigger capital stock than if the economy had remained in recession. The stimulus also helps avert long-term damage to productive capacity – so-called hysteresis effects - such as the loss of worker skills while unemployed, and the dissipation of unique knowledge and skillsets held within firms when they go bankrupt. Lastly, to the extent government spending is on investment goods such as infrastructure, worker retraining, and R&D, rather than on consumption, it will further add to productive capacity.

In sum, stimulus spending during a recession increases not only current employment and income but also the capital stock, and potential future output. During recessions, it could justly, if provocatively, be called “the gift of debt for future generations.”

Estimates of fiscal multipliers – the change in economic output for a dollar of stimulus - broadly confirm that the impact of fiscal stimulus is higher during recessions, in particular when the central bank’s monetary policy accommodates (does not negate) the government’s stimulus effort. The CBO, for example, finds that multipliers for the U.S. average around 1.5 when the economy is well below potential, and the Fed’s monetary policy is accommodative. That is about three times higher than when these conditions do not hold. Another recent paper finds a fiscal multiplier of around one on average, rising to approximately two under an accommodative monetary policy. (See also here and here.)

Since the Fed has pledged to maintain a highly accommodative monetary policy during COVID19, these results mean that, if the U.S. economy is sputtering because of weak demand later in 2020 or 2021, fiscal stimulus will have a powerful effect. A dollar of fiscal stimulus would increase GDP by at least a dollar, and more likely by $1.50 or two dollars.

Consider next the claim that fiscal deficits will cause higher interest rates and inflation, and an unsustainable – unlimited – rise in debt.

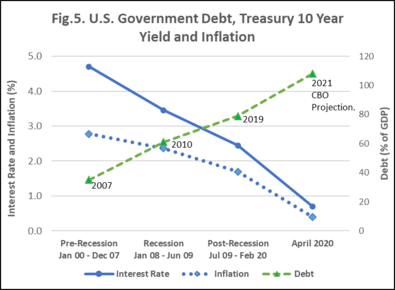

One problem with this claim is a lack of easily visible evidence: U.S. government debt has gone up in recent decades, interest rates and inflation have gone down – a lot. (Figure 5.) Debt jumped by almost 45 percentage points of GDP between 2007, just before  the financial crisis, and 2019, just before COVID19. And yet the average interest rate on ten-year government borrowing fell by more than two percentage points between the period before the financial crisis and the period before COVID19.

the financial crisis, and 2019, just before COVID19. And yet the average interest rate on ten-year government borrowing fell by more than two percentage points between the period before the financial crisis and the period before COVID19.

The CBO predicts COVID spending will push debt to 108% of GDP by 2021. Yet the interest rate on ten-year borrowing slumped to merely 0.7% in April-May 2020. Borrowing at these rates will impose almost no interest burden on the government.

Deficits and debt have also failed to inflame inflation, which has trended lower over the last 20 years. (Figure 5.) Inflation expectations for the coming decade (derived from the Treasury inflation-protected bond market) fell to only 1.1% in April-May 2020. Since investors want to lend money to the government at 0.7%, the real or inflation-adjusted interest rate is negative: -0.4% a year. In other words, investors are so keen to lend to the government they are willing to lose around 4% of the purchasing power of their investment over the next ten years.

A crucial implication of such low real interest rates is that there is no way that debt can rise unsustainably, that is, without limit, under these conditions, or anywhere near these conditions. The equation capturing the ‘law of motion’ for debt is this:

Change in debt = primary deficit + (real interest rate - growth rate of the economy) x debt.

Here debt is expressed as a % of GDP. The primary deficit is the government fiscal deficit before interest payments, also as a % of GDP.

A key implication of this equation is that so long as the real interest rate is less than the growth rate of GDP, debt cannot increase unsustainably. It will always converge to some stable proportion of GDP. But this condition has long been satisfied. The real interest rate averaged around 0.7% in the decade between the financial crisis and COVID19, much lower than the average GDP growth rate of 2.3%.

There seems little apparent reason why this condition would not continue to hold in the future. Analysts have described the overall context as one of “secular stagnation,” where underlying shifts in demographics, technology, inequality, and risk aversion have increased desired world savings relative to investment, substantially reducing equilibrium world real interest rates.

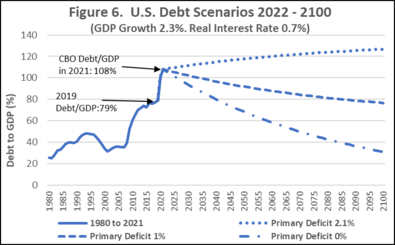

We can use the debt equation to create some scenarios for U.S. debt after COVID19. (Figure 6). Assume the real interest rate and growth are the same as in the period  before COVID, and that the primary deficit comes back down to its average in the five years before COVID, 2.1% of GDP. Then debt would continue to rise gradually, because of continued primary deficits. But it would not grow unsustainably; it would converge to a stable 130% of GDP in the long run. That seems high, but remember that an advanced economy like Japan has been living comfortably for years with debt closer to 200% of GDP, with no sign of a fiscal crisis.

before COVID, and that the primary deficit comes back down to its average in the five years before COVID, 2.1% of GDP. Then debt would continue to rise gradually, because of continued primary deficits. But it would not grow unsustainably; it would converge to a stable 130% of GDP in the long run. That seems high, but remember that an advanced economy like Japan has been living comfortably for years with debt closer to 200% of GDP, with no sign of a fiscal crisis.

It’s true that once stimulus has helped get the economy back to full employment, then the government might have good reasons to reduce debt. They may want to have more space for fiscal stimulus in a future crisis, for example. Or they may be concerned that real interest rates will not always remain lower than GDP growth. Then a modest reduction in the primary deficit to 1% of GDP would put debt on a gradual glide down to a stable 60% of GDP. A primary deficit of zero would altogether eliminate debt in the long run.

Finally – and this point cannot be banged into the heads of Establishment Republicans more strongly – the right time to undertake fiscal consolidation is when the economy is humming along at full employment, not during a recession.

Studies suggest that the premature fiscal consolidation after the 2008-9 financial crisis not only put the American and European economies on a permanently lower growth path, it worsened the government’s indebtedness. Intuitively, an attempt to cut the deficit could increase the ratio of debt to GDP if it reduces GDP by more than it reduces debt. This outcome is more likely during a recession when, as we’ve seen, the fiscal multiplier impact on GDP is high.

In “The Permanent Effects of Fiscal Consolidations,” Fatas and Summers conclude:

“The global financial crisis has permanently lowered the path of GDP in all advanced economies. At the same time, and in response to rising government debt levels, many of these countries have been engaging in fiscal consolidations that have had a negative impact on growth rates…Using data seven years after the beginning of the crisis as well as estimates on potential output our analysis suggests that attempts to reduce debt via fiscal consolidations have very likely resulted in a higher debt to GDP ratio through their negative impact on output. Our results provide support for the possibility of self‐defeating fiscal consolidations in depressed economies…”

Auerbach and Gorodnichenko reach similar findings in “Fiscal Stimulus and Fiscal Sustainability,” pointing to the likelihood of “self-financing” or “debt-reducing fiscal stimulus” during recessions:

“The Great Recession and the Global Financial Crisis have left many developed countries with low interest rates and high levels of public debt, thus limiting the ability of policymakers to fight the next recession. Whether new fiscal stimulus programs would be jeopardized by these already heavy public debt burdens is a central question. For a sample of developed countries we find that the effects of government spending shocks depend on a country’s position in the business cycle. Expansionary fiscal policies adopted when the economy is weak may not only stimulate output but also reduce debt-to-GDP ratios as well as interest rates and CDS spreads on government debt…”

A representative finding by Auerbach and Gorodnichenko is that fiscal stimulus during slumps reduced the debt to GDP ratio by around five percentage points after five years.